Racism and Public Health: Housing

In the first post of this series, we very briefly touched on the various practices that have led minorities in America to have similar disparities related to the social determinants of health. As a reminder, social determinants are the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, and age. In this segment, we will be focusing on where you are born and grow, your neighborhood. For a more comprehensive understanding, we must explore the history of segregation in America. Once we have a more concrete understanding of both the governmental and social practices implemented to divide America, we can then investigate how housing and neighborhoods can in turn impact a slew of characteristics that alter public health.

It should first be noted that prior to the advent of an explicit segregation campaign, emancipated slaves had been outright denied equality of opportunity. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. described this exact reality, in an interview which remains dismally relevant, stating that,

“America freed the slaves in 1863 through the Emancipation Proclamation of Abraham Lincoln, but gave the slaves no land, nothing in reality, and as a matter of fact, to get started on. At the same time, America was giving away millions of acres of land in the West and the Midwest which meant that there was a willingness to give the white peasants from Europe an economic base. And yet it refused to give its black peasants from Africa, who came here involuntarily in chains and had worked free for 244 years, any kind of economic base. And so emancipation for the Negro was really freedom to hunger, it was freedom to the winds and rains of heaven, it was freedom without food to eat or land to cultivate, and therefore was freedom and famine at the same time. And when white Americans tell the Negro to lift himself by his own bootstraps, they don’t look over the legacy of slavery and segregation. I believe we ought to do all we can and seek to lift ourselves by our own bootstraps, but it’s a cruel jest to say to a bootless man that he ought to lift himself by his own bootstraps”

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., NBC

In the introductory article, we briefly discussed the history of de jure segregation. De jure segregation refers to specific action taken on behalf of governmental entities to restrict minorities to specific communities. According to Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law, this phenomenon began with the creation of segregated public housing. Public housing was initially intended for white defense workers and their families because there was a lack of housing during the First World War. People of Color (POC) were specifically barred from these facilities. The Second World War brought with it a severe housing shortage as an influx of workers bombarded cities for manufacturing jobs. The industry tried to maintain a whites-only workforce but inevitably needed a greater labor supply. The Roosevelt administration’s Public Works Administration (PWA) sought to rectify this and maintained a “racial composition rule.” The rule claimed that federal housing projects would honor the previously established racial distinctions from neighborhood to neighborhood. However, the PWA specifically segregated communities that had been integrated prior to their involvement in Atlanta, St. Louis, Cleveland, and many more cities across the nation. More specifically, the Techwood Homes project in Atlanta was accomplished by leveling an integrated community that was home to 1600 families, one-third of which were Black, so that 604 units could be established for whites only (citation pg. 21). As recently as 1984, reporters for the Dallas Morning News had visited 47 federally funded developments and concluded they were almost always segregated by race and those that were predominantly white had far more quality amenities.

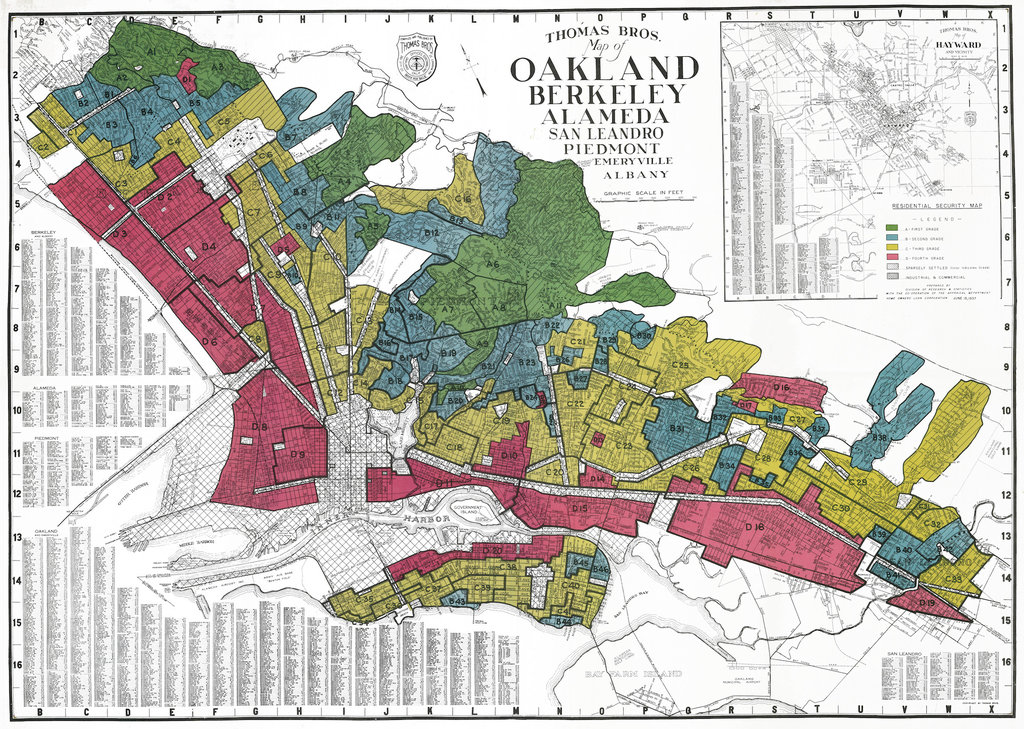

“City maps were graded according to an ‘A’ through ‘D’ scale and color, the red ‘D’ list neighborhoods just so happened to coincide with minority communities.”

The most often cited strategy employed by our government is referred to as redlining. Redlining has come to mean discriminatory housing practices in general, but the term specifically refers to New Deal-era policies. Cities, like Miami, had adopted racial zoning ordinances which prohibited Black folk from purchasing homes on blocks with primarily white residents and vice versa. When the Supreme Court decided in Buchanan v. Warley (1917) that this outright discrimination on the basis of race was a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment, bigots had to get creative. Utilizing Northern city planners’ ingenuity to manipulate our legal system, cities across the nation were divided up according to “risk.” City maps were graded according to an “A” through “D” scale and color, the red “D” list neighborhoods just so happened to coincide with minority communities (citation). Lenders were warned against giving out loans in these parts of town and the federal government would also refuse to insure mortgages. These zoning laws were made that much more insidious by their specific industrialization with allowances made for pollutant industry, liquor stores, nightclubs, and brothels in the minority communities and strictly barred from white neighborhoods.

Ironically, in Miami, “Colored Town” prospered thanks in part to white patrons seeking after-hours drinks at establishments such as the Mary Elizabeth’s Zebra Lounge. White tourism failed to dissuade a campaign of terror launched on the community by some 400 deputized American Legion members though. This was unfortunately not an isolated incident across the nation. Black folks had prospered and built widely successful communities, but this was incongruent with white supremacist standards and thus they were met with economic terrorism. The Greenwood district in Tulsa, Oklahoma was colloquially known as “Black Wall Street” before it was burned to the ground. Springfield, Illinois was similarly razed for having the audacity to exist. Although, some were able to flourish by hiding their wealth like those in Durham, North Carolina. Recognizing this destructive trend, Black residents employed survival tactics and chose not to flaunt their wealth as to hide it from prying eyes. The social policing of Black excellence at the hands of mobs of white people served to reinforce the specific segregation enacted by the government.

“Black folks had prospered and built widely successful communities, but this was incongruent with white supremacist standards and thus they were met with economic terrorism.”

Now that we understand how governmental and societal factors have worked in tandem to condemn POC to specific parts of town, we can investigate how this impacts health outcomes. When we consider how there have been specific efforts made to industrialize minority communities it is no wonder that hazardous waste facilities are found in abundance. Researchers at the University of Michigan found, “a consistent pattern over a 30-year period of placing hazardous waste facilities in neighborhoods where poor people and people of color live.” Not only are POC subjected to the harmful effects of close proximity to hazardous waste, but the air quality they are subjected to is often incredibly subpar. University of Illinois researchers also found that,

“Black people were exposed to higher-than-average concentrations from all major emissions groups, while white people were exposed to lower-than-average concentrations from almost all categories. The disparities were seen nationally, as well as at the state level, across income levels and across the urban-rural divide.”

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Researchers

In addition to hazardous waste facilities and air pollution, there is a strong correlation between redlining practices and tree cover. One study found that “areas formerly graded D have 21 percentage points less tree canopy than areas formerly graded A.” These are just a few of the ways that the specific location of your neighborhood can lead to disparate outcomes which in turn impact health.

Where someone lives also impacts a number of social determinants that we will continue to explore throughout this series. For example, education is directly linked to where you live considering property taxes fund local public schools. We will also take the time to explore how dietary habits impact health and how food deserts are often found in minority communities. Of course, we will also be working to better understand how community violence and over-policing directly impact health outcomes.